In line with labyrinths and thinking paths, like-minded people merge talents to create earth drawings that focus and transform energy . . .

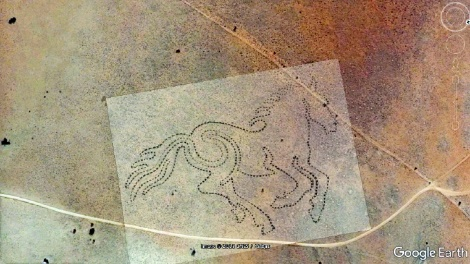

It’s a blustery day at Klein Aus Vista in south-western Namibia when I meet up with the Land Art group. The brightly-dressed happy bunch, seemingly oblivious to the weather, are hammering old fence droppers into the ground in areas marked out with pieces of string. The land stretches out around them in a soothing medley of earth colours, backed by rocky granitic-gneiss hills. I am directed to Anni Snyman in her generous red hat and her brother PC Janse van Rensburg, the pair who have combined skills to create a series of geoglyphs – or earth drawings. Between the hammering and wind, I hear their story – and discover the 100x150m galloping wild horse that will emerge in the landscape by the end of the week.

“We call them thinking paths,” Anni tells me. “We normally make walking paths. The whole illustration is always one line so that if you start walking from one point, you’ll find yourself back where you started. It’s like a mediation path – a labyrinth.”

The third geoglyph to be created by the siblings and their team of volunteers is unlike the two they have previously worked on in the Karoo - a Snake Eagle in Matjiesfontein and a Riverine Rabbit in Loxton - because of the sensitivity of the Namib Desert environment. Visitors won’t walk this path, but will walk up to the viewpoint on the nearby koppie to see the horse galloping across the plains. This concept of adapting to the environment and the terrain fits in admirably with the name of the project – Site Specific.

Being acquainted with the pre-Columbian Nazca lines etched onto the vast Peruvian desert sands, I soon realise that like the ancient renderings these geoglyphs can also only be viewed from a height – with the help of Google Earth, a drone, a hot air balloon or in this case, a koppie. “It’s a bit like life,” Anni explains. “You can’t see the path in front of you, but you are making a path. Perspective is always the thing.”

Anni and PC first heard about Klein Aus Vista Lodge near Aus and its owners, the Swiegers family, from a mutual friend who planted the idea of creating a geoglyph there three years ago. Honouring the century-old population of Namib wild horses, a major tourist attraction in the area, Anni and PC decided to use the image of a wild horse for their geoglyph. Appearing to run towards the crossroads, the horse is intended not only to make people aware of the fate of the population whose existence is presently under threat, but also to think of our place as human beings on the planet, with the increasing and startling effects of climate change on our doorstep. The Swiegers donated the old fence droppers to be used to mark the image, apt material to emphasise this image of rewilding and hope.

“Salute!” I hear behind me, as PC buoys the spirits of the volunteers on the chilly day with his good cheer and tots of Old Brown sherry – doled out in small plastic glasses. The laughter echoes across the land before they make their way to the rustic Geisterschlucht (Ghost Valley) stone cabin, which the Swiegers have offered to the group as a snug home for their stay.

I follow their bubbling laughter to the cabin, where Ouma Lettie, Anni’s mom, who is taking a break from her Brahman cows in Sasolberg, has laid out a feast. Around the long wooden table, with a fire lit, I learn that the volunteer group comprises people who have an artistic inclination and a love for nature and the Earth. Most have joined Anni and PC before on their projects, or have met at the art biennales and at the Global Nomadic Art Project, making it a warm gathering of friends. “Most of us have a good dose of art in us, and have been lecturing and teaching art at some stage,” Anni tells me. The volunteer group is never fixed, it depends on who is available, who can take leave from their jobs “and whose wives allow them to come,” PC adds. And they hail from all around South Africa - from Joburg, Pretoria, Plettenberg Bay, Loxton and Cape Town. “And don’t forget Ma the cook from Sasolberg,” Ouma Lettie pipes up.

As a professional artist, Anni draws the exquisite designs for the Land Art, while PC complements her with his expertise as an architect to make all the proportions gel, quite a feat for these gigantic works of art, only able to be viewed in their entirety from above. The design is laid out on a grid system, to be transferred later, massively enlarged, onto the land. The wild horse geoglyph is proving to be challenging as the slope of the land is affecting the proportions and extra droppers are needed to thicken the line. This doesn’t deter the group or dull their mood. The stories of their other two major geoglyphs unfold as the food sizzles on the fire and glasses are raised in celebration and gratitude.

The 170x57 metre Snake Eagle in Matjiesfontein made in 2015, funded by the Lord Milner Hotel, ClemenGold and Umvoto, was intended to bring attention to the proposed fracking in the area. The image of the grand eagle with wings outstretched and a spiral running through its centre has become a landmark in the area and was even used as one of the final clues in the Sunday Times’ Finders Keepers competition in 2017. Keeping an enlightened attitude Anni says, “We realised that you can’t just protest against something because the people in the area need an economic source, so we thought that as artists we could assist ecotourism and protest at the same time.” When they were wondering what image to create, a pair of Black-chested Snake Eagles circled above, presenting the answer.

In 2016, they created a 104.5x90 metre Riverine Rabbit Thinking Path (Doekvoetdenkpad) in Loxton, one of the last places you can still find this small creature endemic to the central Karoo and listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of threatened species. Using a swathe of degraded land that had previously been used as a sheep farm and abattoir, the team set about transforming the space and instilling a more positive energy. As with the Snake Eagle, the line of the image was drawn with large circles painted with limewash at 30cm intervals, which means that people walking the paths are essentially ‘connecting the dots’. The Endangered Wildlife Trust, who is running a project in the area to protect the remainder of the species, donated indigenous plants to stabilise the sand, nurturing Anni’s dream that the land would one day be planted with medicinal Karoo herbs. The community was invited to be part of the project. A local artist engaged the children to make rock pigment and paint the rabbit’s favourite plants on the walls of the old slaghuis, which was converted into the Huis van Tyd – House of Time. The older folk gleaned some tasty home recipes from Lettie on her week-long cooking course, “like boontjies, marmalade and the best fig and apricot jam that you have ever tasted in your life.” Community garden and recycling co-ops were set up at the site and the house was made available for the local needlework group. Calligraphy artist, Andrew van der Merwe, contributed his skills painting and detailing the life of the Riverine Rabbit and performance artist, Allan Booysen from the Grrr Kollective, drilled holes in the roof in the shape of the rabbit, so that when the sun moves across the sky, the rabbit glides across the building in dots of light and sunshine.

Anni and PC’s collection of Land Art also includes a two-tailed Earth Siren made at AfrikaBurn in 2008 and 2009, inviting Burners to contemplate how we treat our Earth home while they walk it. All the land art is essentially temporary. Anni says, “If it disappears, it will create a blank canvas for the next artist to do something.”

The team is often asked why they make things they can’t sell. Anni says that’s exactly the point. It’s not divisive. It becomes accessible. It cuts though religion, history and racism to reach everyone. With art having been wiped off the syllabuses at many schools, she sees it important to make art a community event.

Although supported by many, the core of the Land Art projects are Anni’s well-executed drawings. Her fascination with labyrinths and one-line drawings stems from artist Alexander Calder, who spent years drawing animal shapes with one line, trying to capture the essence of the animal. “At the time I came across him,” Anni tells me, “I was working at the Cultural History Museum in Pretoria, so at every lunch break I would go to the zoo and see if I could draw an animal with one line. It has been a fascination with me for many years and has now come full circle.”

I have a better idea of the concept of Land Art, an unobtrusive way to collaborate with the environment, the Earth and people when I leave the warm cabin and walk out into the starry night, where I now know a wild horse will soon gallop across the vlakte.

The next morning, I stop by the site to say my farewells. I notice that the team has made the necessary adjustments to the image and is efficiently following the new grid pattern to rectify the image so it can be viewed in proportion from above. And I remember something that was mentioned the previous night. They entertained the idea that with more of Site Specific’s geoglyphs being created, it would soon be possible for people to travel - and walk - the geoglyph route on a type of Geoglyph Camino. I mull that over as I drive out into the sunny blue-sky day, thinking what a fine idea that would be for a journey, to walk the thinking paths of the Earth.