Angels followed me around Ethiopia. Depicted as illuminated heads with wings, the Ethiopian angels peered down from church ceilings in Gondar and from the colourful painted friezes of the circular island churches on Lake Tana.

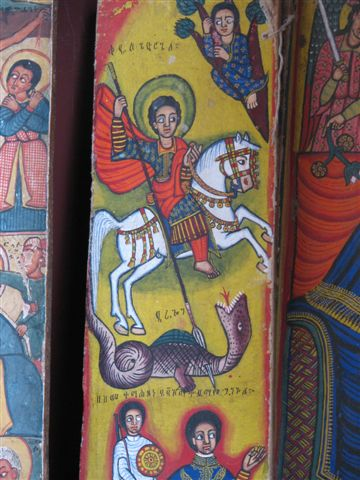

Ethiopia has emerged out of the mud of mediocrity to shine brightly with intriguing, surprising and serendipitous characteristics and qualities. Laying down the old fraying photographs of famine, perceptions of the past, and bypassing the huge population explosion that is Ethiopia today and the children that shout “you, you, you” as you pass, prepare to be charmed by its idiosynchrocies, anomalies and individuality. St. George, a favourite patron saint, sitting astride his white steed, is emblazoned everywhere from the local beer to religious icons, churches and coins. He hints at the oddities that greet your arrival in this North-East African country whose inhabitants speak Amharic, eat fermented tef pancakes with spicy sauces, have elaborate coffee ceremonies, a Julian calendar seven years behind ours, an alternate concept of time, Italian words peppered into their language and culture from a five-year occupation, and an ancient form of orthodox Christianity.

In the fourth century Christianity was adopted in Axum, in the northern highlands of Ethiopia. The Orthodox Christianity of Ethiopia has its roots deeply embedded in the Old Testament, the Ark of the Covenant of Judaic tradition having a symbolic place in its churches. Hidden away from the rest of the world for centuries, the old Coptic traditions were retained. Ge’ez, an ancient language similar in script to Amharic which descended from it, remains the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

North of Addis Ababa - shrouded in pollution, with people herding sheep amidst thirty-year-old Russian Lada taxis - the route to Lalibela heads into the highlands where patchwork quilts of green and brown fields create mountain tapestries, dotted here and there with old Italian stone bridges. Lalibela pokes her head out of the mountainous terrain amidst the clouds and astonishes the traveller once again. She is renowned for her rock-hewn churches, dating back to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The mastery of the buildings carved out of rock in a time before modern technology is a marvellous and mysterious feat. According to legend, the work that King Lalibela completed in the day was matched by the angels’ contribution at night.

Following our guide through the maze of red rock churches, we stepped into the past. It was not into the stagnant air of a museum but into sacred places well-used in the wonderful way Ethiopia has of combining the old with the new. People sat on carpets, singing in Ge’ez, drumming and swishing their sistrums, while a wedding party on the opposite side of the church received blessings from a priest brandishing a holy Lalibela cross. As we walked through the labyrinth of monolithic churches St. George looked down from a painting on a church wall, Mary and child glowed from another and prayer sticks balanced in a rock-hewn corner. People dressed in white traditional scarves leant against pillars polished by centuries of worshippers and the drone of singing rose up into the high ancient ceiling. It was easy to imagine a host of Ethiopian angels sitting up above watching this fusion of ages.

The priests in all the churches were surprisingly amenable to having photographs taken, one wearing sunglasses to protect his eyes from the camera’s flash. Walking around the ancient rock churches, I came across a young slender girl in a white dress and headscarf who befriended me, followed me, exchanging shy smiles and the universal warmth of companionship. Eventually I felt her soft hand in mine as a goodbye and saw her peep through a doorway and wave. A thin cat lying in front of the church sidled up to me, rubbing against my legs, and then disappeared. I felt the ancient energy, the coolness of hundreds of years of memories flowing like a breeze through the churches.

We settled the overload of stimuli and time-travel over lunch, and in the afternoon drove the eight kilometres to an outlying church constructed under a rock ledge in the mountain, surrounded by dry hills. We lay on mats spread out on straw that was scattered over the stone floor and breathed in the peace of the place, while the rain fell outside and the holy water dripped down from the mountain. The shoe-minder outside sat haloed with a view of the valley behind her, our shoes surrounding her in a semi-circle of paired shapes.

Walking the cobbled Lalibela roads in the evening, we located a small bar and sampled a honey-mead drink called tej from glass vials. I looked around me as the sweet fluid sent strange taste sensations to my brain and competed with the day’s out-of-the-ordinary fullness. The walls of the tej-house were decorated with Ethiopian angels, and the small heads framed with wings continued to bless our way.

Info Box:

The rock-hewn churches of Lalibela were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1978

There are 11 churches carved out of bedrock with their roofs at ground level and steps leading down to their entrances

Each church has its own priest

Shoe-minders take care of your shoes, which you are required to remove as you enter

To best navigate through the churches, have the sites explained and follow correct protocol, it is advisable to hire a local guide

Lalibela was originally known as Roha, a name given to King Lalibela when a swarm of bees surrounded him at birth, a sign of his future deity. It is recorded that King Lalibela had a dream where he was instructed by God to build the rock churches as a New Jerusalem.